The spring of 1921 was a time of intense class conflict. In Russia, the government was engaged in a head on clash with its critics, whilst in America the Coal Wars were heading towards a bloody conclusion on Blair Mountain.

Germany, the heart of Europe, was also deeply disturbed. Reeling from military and political collapse, industrial disputes were endemic. In most places, however, the working class was on the defensive, smashed by repeated blows from a military machine made vicious by defeat and wielded by the best organised and most power hungry politicos in the world – the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD).

One of the islands where the workers remained unbowed was the Prussian province of Saxony (now part of Saxony-Anhalt state). The south of this area, around Halle, was an important industrial area. Immediately south of the city was the vast Leuna chemical works fed by gigantic opencast brown coal mines, whilst in the mountains to the west was a major copper mining region, centred on the towns of Mansfeld and Eisleben.

On 17th March 1921, tired of ceaseless strikes, sabotage and thefts, the Social-Democratic government announced their intention to occupy and pacify the mining district. Chief architect of the campaign, Carl Severing, Prussian Minister of the Interior, a high placed Social-Democrat, used the occasion to test the new armed “security police” (Sicherheitspolizei – the Sipos or Sips) rather than the army. Severing was party to the conspiracy with the generals in the creation of the so-called Black Reichswehr, and later, as national Interior Minister, helped prepare the ground for Nazi oppression with attacks on free speech and assembly.

An important factor in this decision was the rise of the Communist Party (KPD). At the end of the previous year, the KPD had absorbed the bulk of the Independent Social-Democratic Party (USPD) to become the party of the far left. Now half a million strong, on 20th February the KPD had won state elections in Merseburg – precisely the area now targeted. Bolstered by election success and targeted by Comintern representatives such as Béla Kun (former leader of the tyrannical state socialist government in Hungary), the KPD had also decided on a confrontation.

The KPD’s new stance was also influenced by its external left – the Communist Workers’ Party (KAPD). This anti-parliamentary group had been formed the previous year in the wake of the KPD’s failure to capitalise on, or even meaningfully participate in, the resistance to the Kapp Putsch and was achieving some degree of success. Given the deviousness of the “Communists”, one cannot rule out the possibility that this “turn” was intended to be a demonstration of the uselessness of the KAPD’s strategy. Certainly the lack of effective support from Central and the rapid reversal of the “insurrectionary turn”, suggests that, so far as the KPD is concerned, the “March Action” was set up to fail.

On 19th March, the security police arrived in Mansfeld and Eisleben. The area was placed in lockdown and house-to-house searches in search of weapons commenced. Two days later the Leuna works’ council (the powerless bosses’ replacement of the workers’ councils) was deposed and a joint KPD-KAPD action committee elected. Although disorderly (as the forces of order usually are), there was nothing very much out of the ordinary. And then Max Hoelz arrived. Hoelz was the son of a poor agricultural labourer. Through hard work and study, he advanced to become a surveyor, eventually settling in Falkenstein in western Saxony. Like many others, his service as a soldier radicalised him. After the war, he became an activist for the unemployed, not hesitating to requisition food and fuel for the distressed of the town and going so far as to imprison the mayor and town council for calling the jobless “work-shy parasites”. It was, however, during the Kapp Putsch of March 1920, that he rose to fame, organising a Red Guard. A contemporary describes their makeup:

“The commando, motorised, counts 60 to 200 men. In front, a reconnaissance group with machine rifles or lighter arms: the heavily armed trucks followed. Then the “chief” in a motorcar, “with the cash” in company of his “minister of finances”. As cover, another heavily armoured truck. All decorated with red flags. From their arrival in a locality, provisions are requisitioned, the post offices and savings banks are ransacked. The general strike is proclaimed and paid for by the employers with a “tax” levied. Butchers and bakers are ordered to sell their merchandise 30 to 60 per cent cheaper. All resistance is crushed immediately and violently…”

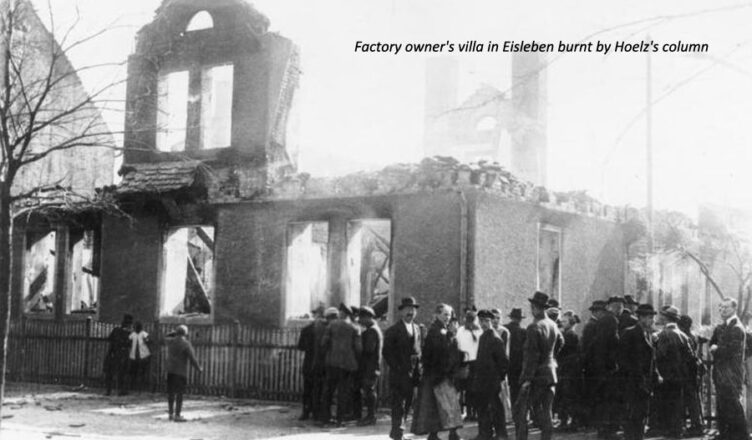

The Robin Hood of the Vogtland roamed the countryside burning the villas of the rich, destroying tax records, freeing prisoners and distributing booty. He was, naturally, extremely popular with the poor folk. After the end of the Putsch, the army occupied the Vogtland and Hoelz vanished. On the 22nd, he reappeared in Mansfeld and, on the following day, the March Action really began.

Making incendiary speeches, the rebel Hoelz spurred the locals into action. Miners and the unemployed were supplied with weapons and another campaign of villa burning and bank robbery began. The local newspaper offices were blown up and troop trains derailed. The 2,500 strong column had a smashing time!

Meanwhile, at the approach of the Sips, the Leuna came out. Here, however, the workers confined their activities to defence and the construction of an armoured train (whose purpose, given that the rails in the area had been pulled up by the column, remains a mystery). Within the works, disputes between the various types of communist arose. All concerned, of course, condemned the “adventurism” of Hoelz.

Faced with the escalation, the President of Germany, Friedrich Ebert, declared a state of emergency on the 24th. The Communist Party, in turn declared a national general strike.

In the event, the anticipated general uprising against the government, on the model of the response to the Kapp Putsch exactly a year before, failed to materialise. Not only was armed activity at a minimum but the general strike, a tactic which had brought the Putschists of ’20 to their knees, was a non-starter. On the 29th, the Leuna was forced into surrender. 34 workers had been killed, mostly summarily executed, and 1,500 prisoners taken. The last armed group was broken up in Beesenstedt on April Fool’s Day. The total casualties were 180 dead, including 35 police. A very light toll compared to similar actions by the army. 6000 were arrested, around half of whom, including Hoelz, received jail terms.

The “March Action” was a last desperate attempt to unleash the collective power of the working class. But the hold of social-democracy and the trade unions, not just physically, in their institutions, but mentally, in the inherited legalistic and hierarchical mindset, was too strong. On the part of the Communist Party, it had been a cynical attempt to use an existing dispute to seize power. Even in the affected area, to go against “democracy”, even when that “democracy” was visibly on the side of the enemy, against one’s own interest, even, in some cases, against one’s own self-preservation, was taboo.

The response of the Communist Party was predictable: A retreat to the legalistic parliamentarianism, working within or with the trade unions and existing left parties, prescribed by Grand Master Lenin in Left Wing Communism – an Infantile Disorder:

“…you must soberly follow the actual state of class consciousness and preparedness of the whole class (not just of its communist vanguard), of all the toiling masses (not only their advanced elements)” straight into the ever loving arms of the class collaborationist social democrats.”

The “lesson” for the anarchist is less clear. Hoelz’s “Propaganda of the Deed”, understandable as it might be in the circumstances and enjoyable as it undoubtedly was (imagine seeing Jeff Bezos’s house disappearing in smoke – just think of it now, don’t, of course, do it), generated as little response as the connivings of the “Communists”.

But anarchist/communists are not glorified Luxemburgists or Situationists looking to attentats to generate good little party workers or to smash some putative “spectacle” of the mind. Like any seed, to bear fruit the word of the anarchist/communist must fall on good ground. Without education and organisation, the fostering of industrial and community self-activity, any revolutionary talk will fall on stony ground.

“Hölz’s army dominated the region for ten days, but only fought particular aspects of capital without changing anything essential. It was primarily an armed gang which executed certain operations. The proletarians constituted themselves as a military force but would not change anything. Their violence remained without an objective, and destroyed the visible enemy, but not the enemy’s roots. It was a negative movement. Occupied by close to 2,000 workers, the industrial complex of Leuna was not directly utilized for revolutionary ends. One part of the proletarians remained outside of the workplace and fought without the social weapon which, for the proletariat, is production. The other part shut itself up within the factory. There was neither any coordination between these two groups, nor was there any concentrated employment of military force against the State. The movement ran out of steam due to both its purely military generalized offensive, and because it had ensconced itself at the point of production. Hölz robbed money, but he did not abolish it.”

Gilles Dauvé and Denis Authier, The Communist Left in Germany 1918-1921

https://libcom.org/library/chapter-15-march-action-1921

“The Executive Committee and its representatives in Germany had already been insisting for some time that the Communist Party, by committing all of its forces, should prove that it was really a revolutionary party. As if the essential aspect of a revolutionary tactic consisted solely of committing all one’s forces… On the contrary, when, instead of fortifying the revolutionary power of the proletariat, a party undermines this power by means of its support for parliament and the trade unions, and then, after such preparations (!) it suddenly decides on action and puts itself at the head of the same proletariat whose strength it had been undermining, throughout this entire process it cannot ask itself whether it is engaged in a putsch, that is, an action decreed from above, which did not originate among the masses themselves, and is consequently doomed to failure. This putsch attempt is by no means revolutionary; it is just as opportunist as parliamentarism or the tactic of infiltrating cells of party members into all kinds of groups.”

Herman Gorter “The Lessons of the March Action”, L’Ouvrier Communiste, May 1930

https://www.marxists.org/archive/gorter/1921/march-action.htm

“Two years ago, I still believed that the communist idea, the concept of emancipating the proletariat, could be carried out by means of an economic struggle, without the use of force. At the time I would have been ashamed to shake hands with someone like myself today. But when the revolutionary working class uses force, it does so only in response to the violence that the ruling class unleashes against the proletariat’s existential struggle and its attempts to raise itself up. It is the ruling class that was first to use violence. When a communist speaker appears today before a gathering and proclaims his views, he is persecuted, and violence is used against him. Yet every use of violence by the oppressed class is branded by the bourgeoisie’s public opinion as an injustice, as a crime. The ruling class grants us freedom of expression and freedom of speech only on paper. In practice, communist newspapers are banned, and communist assemblies prevented – all by means of violence.”

Max Hoelz, “Indictment against Bourgeois Society”, Franke Verlag, 1921

https://www.marxists.org/subject/germany-1918-23/hoelz/indictment.htm