This month promises to be a liberal jubilee, first the triumph of the Jacinda Ardern the saviour of New Zealand and then, unless the polls are very wrong, the election of Joe Biden and humiliation of Donald Trump. After their foolish support for populist parties voters have finally woken up and realised that the technocrats were right all along. Even Kier Starmer’s Labour has made some ground in the polls.

It is a rosy picture for the anti-populists and already the suggestions to ensure that another Trump won’t get into power are being made – statehood for DC, abolishing the electoral college, etc. Key to note is that nearly all these suggestions to stop populism are electoral, proposals to make the system more “democratic” – and more Democratic.

Proposals to address populism politically (even within a liberal political framework) are noticeably absent. So long as populists parties do not have electoral power they, and those that vote for them, can simply be placed on the naughty step until they have learnt the error of their ways, meanwhile the grown-ups can get on with governing.

This focus on electoralism is a continuation of the strategy that anti-populists have used, with diminishing returns, for the last twenty years. The French electoral system is deliberately ‘biased’ against the National Front/Rassemblement National (FN/RN), yet the support for the party has both expanded and deepened over the years. In the UK First Past the Post system may have denied populist parties MPs, but the last 20 years have produced the two most electorally successful hard right parties there have been. And while there is evidence that the COVID-19 crisis may be causing voters to favour a return to the establishment for the present, populism is very far from being dead and buried. Ardern and Biden have taken up more space in the press, but in the recent Italian regional elections the populist radical right consolidated their strong level of support.

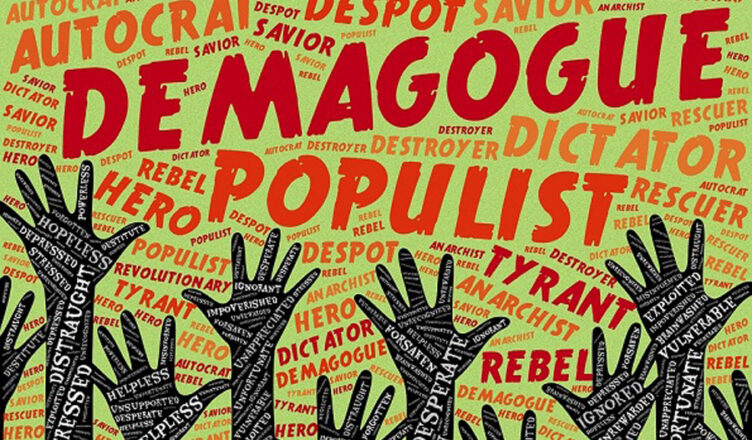

Fundamentally liberal anti-populism is incapable of dealing with the “problem” of populism as populism is part of the liberal democratic system. But anti-populism is not merely ineffective, from a pro-working class perspective it is actively harmful. The constant attempts of anti-populism to “expertise” politics, reducing areas of class conflict to scientific/technocratic questions has resulted in significant material losses to the working class. At the same time many traditional centre-right (and centre-left) parties have been willing to follow the line of populist radical right parties on cultural issues, such as anti-immigration rhetoric and policies, hoping for an electoral pay-off (a tactic that normalises populist ideas, providing further opportunities for the growth of populist parties and showing how the political power of populists can be greater than their electoral strength).

In most of North America, Western Europe, Australia and New Zealand there is a cap on the level of possible support for populist radical right parties. As such, it is relatively easy for anti-populists to design electoral hoops that ensure populist radical right parties can be pushed out or excluded altogether from the electoral system. The fear of the populist right has caused some to retreat into anti-populism, but your enemies enemy is not your friend. By strengthening the power of the working class, opposition to anti-populism is a means to combatting the radical right.