The rebellion against the regime of Umar al-Bashir in Sudan started in the northern city of Atbara, a railway terminus, in December 2018. Discontent against a regime that had brought poverty to the mass of the population erupted with the cry “tasqut bas” (it should just fall). The headquarters of the ruling National Congress Party was burned down, and the police replied to this with tear gas and live ammunition.

The revolt erupted again on April 6th, having spread to the capital, Khartoum. The police and military attacked the demonstrators, killing over 120 people, and using tear gas, rubber bullets and again live ammunition. Thousands were arrested. The government had declared a state of emergency in February, shutting down the press or censoring it, applied restricted access to several phone companies, and disrupting the internet.

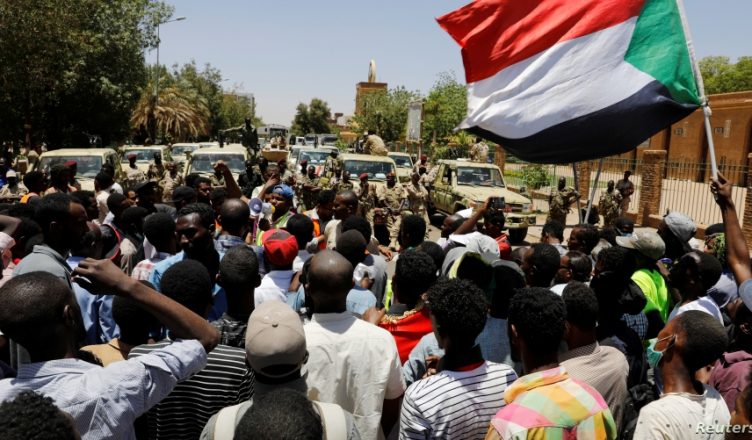

Despite this, the demonstrations continued. Several thousands set up a camp outside the main army base in Khartoum and demanded that al-Bashir be removed as President.

The protests were initiated by the Sudanese Professionals Association (SPA), made up of doctors, lawyers, journalists, engineers, teachers, and university professors. Their demands have been vague with calls for “Freedom, Peace and Justice”. However, the working class has involved itself in the demonstrations, and the Sudanese Jobless Association had its banners on demonstrations. Up to 70% of those involved in the demonstrations have been women, and they have shown great courage and determination.

Al-Bashir has ruled Sudan for almost 30 years. He is the only head of state wanted by the International Criminal Court for war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide, as the result of his policy of ethnic cleansing in the Darfur region. The protests began when the government ended subsidies of basic goods. This was an attempt to tackle the rate of inflation, which stands at 122%, the second highest in the world. Almost half the population live below the national poverty line, with 5 million people facing food insecurity. 20 percent of Sudanese men and 40 percent of women are illiterate. Seventy per cent of the national budget is spent on the military, and only 5 per cent on healthcare.

But on April11th, al-Bashir was ousted. He was put under arrest by the military. Later on, in a scenario that has parallels with the ousting of Mugabe in Zimbabwe, the Minister of Defence said that it was overseeing a two-year transition leading up to elections. Parliament was shut down, as was the government and local state governments. As state of emergency was imposed for 3 months, as well as a 10pm curfew. However, the demonstrators were not prepared to put up with this, calling for protests to continue and developing slogans against the military government. Anti-Islamist sentiments began to emerge amongst the crowds.

The Army was forced to intervene because dissent was growing in its own ranks, whilst on the other hand the security forces, made up of Islamist militias, defended al-Bashir. These militias killed 5 soldiers who were trying to stop violence against the crowds. The Army leadership is terrified of revolt amongst the rank and file and the junior officers, which is why it made its move.

However, the Sudanese masses have seen the recent example of Egypt, where the Army took over from the old regime, and imposed something even worse. They do not want a military government.

This military ruling council was led by a former Vice-President, Awad Mohamed Ahmed Ibn Auf, surrounded by other veterans of the al-Bashir regime. The crowds refused to accept this, chanting “The revolution has ony just begun” and “We won’t replace Koaz (An Islamist leader) by another, Ibn Auf we will crush you, we are the generation that will not be fooled”. The continuing protests meant that the military council had to remove Ibn Auf within twenty four hours. Demands now came forward for the arrest and prosecution of leading members of the regime and the end of austerity measures.

The new head of state, Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, promised to carry out the will of the people. But the murderous thug Salah Gosh, who was head of intelligence, was allowed to resign instead of being arrested, and the whereabouts of al-Bashir was kept a secret by the military. The chief public prosecutor and the head of the state run radio and television were also allowed to resign rather than be arrested. Meanwhile many political prisoners are still behind bars.

It was then discovered that the SPA had begun negotiating with the military council. This provoked outrage among the crowds.

In May, armed thugs attacked the crowds, killing four people. The head of the military council, Burhan, now began demanding that blockades on roads and railways be removed.

In response, a massive general strike broke out. In Khartoum, the response to the strike call was almost 100 per cent. The strike affected, the banks, ministries, schools, hospitals, airports, power plants, mines and ports.

In some places the counter-insurgency forces, the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) led by Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, deputy of the military council, arrested 10 striking electricity workers, but were forced to release them after other workers threatened to cut off electricity supplies. In southern Khartoum the RSF fired on workers at a fuel pumping station, seriously wounding two.

On 3rd June, the military attacked and cleared the sit-in in front of the Ministry of Defence in Khartoum. At least 13 were killed. Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo has been whipping up hysteria among the RSF militia, claiming that the unfolding revolution was anti-Islamic. The most dissident Army regiments, meanwhile, were confined to barracks.

The RSF then began rampaging through Khartoum over the following days, dismantling barricades, beating up and flogging protestors and raping women. At least a hundred people were killed and their bodies thrown in the Nile.

Meanwhile the military council announced that it was organising elections within 9 months, in a bid to defuse the movement. But on 9th June, another general strike broke out and several large demonstrations began. Either the repression will crush the developing revolution or it will cause increased resistance. Dissent is growing rapidly within the military, and many may side with the masses against the military council and the RSF thugs. This remains to be seen.

Black Autonomy – Call for Solidarity with the Rebellious People of Sudan

Source: Black Autonomy Network

Since the middle of December last year there has been an ongoing revolt in Sudan. This outbreak of rebellion a continuation of earlier struggles against the regime of Omar al-Bashir. In April, escalating protests led to a round the clock sit in occupation of the Military HQ demanding the fall of the regime. The military – under the pretext of siding with the revolutionaries – used this unrest to stage a coup and oust al-Bashir and install themselves as the Transitional Military Council(TMC), many of the people on this council had ties to the old regime and to the notorious Janjaweed – an Arab ethno-nationalist militia (re-branded under al-Bashir as the Rapid Support Forces or RSF) involved in war crimes and genocide in Darfur.

The TMC tried to negotiate with the movement to form a government, but the people of Sudan saw this for what it was, and while negotiations were ongoing people were determined to hold the sit in. Negotiations broke down as the movement demanded a full civilian government and Saudi Arabia, the UAE – regional powers who contributed to the counter-revolution to the Arab Spring – and Egypt pledged political and economic support to the military council as they pushed to hold onto power.

The TMC began to criminalize the protests and declared the sit-in a “security threat”. Only days after the declaration the RSF attacked and cleared out the sit in with live ammo and burned down the tents at the sit in while the army watched. The RSF continued on a rampage all over Khartoum with a confirmed count of over 100 dead and 650 wounded.

More pictures of barricades built yet the RSF patrolling through them on the streets of Khartoum. Exact location/time unknown, but taken today and been circulated around. @BSonblast @YousraElbagir @daloya @AJEnglish @ReutersAfrica #SudanUprising #Google_Open_Internet_For_Sudan pic.twitter.com/VPgDAi1Cry

— Anavi mxb (@ana_fi_anavi) June 4, 2019

The RSF occupation of Khartoum is still ongoing and the TMC has had the internet shut off for over 72 hours making reports of what’s going on hard to come by, but calls have come from the movement for “total civil disobedience” and there is sporadic video and text of people resisting all over Sudan.

“current situation:

– resistance activities at peak, w/ most roads barricaded

– intermittent sound of gunfire heard across neighborhoods

– call to prayer made in most neighborhoods; in some, RSF prevented ppl from attending, in others people insisted on fasting”#SudanUprising https://t.co/Jg7BChIbHw— Munchkin (@BSonblast) June 4, 2019

Why Does This Matter

Let’s be clear, what’s at stake is the spreading of a rebellious energy across the Middle East and the African Continent that threatens the political order. That’s why regional powers and allies of the US – Saudi Arabia and the UAE – have supported the TMC and their repression of Sudanese rebels.

We find ourselves in a moment of international right wing reaction with fascistic, white supremacist, and other authoritarian movements and states seizing or consolidating power all around the world. Our enemies have spent many years networking and building internationally, capitalizing on both human and environmental crisis, but these crises don’t have a single road out that leads to authoritarian power that we try desperately to react to. These moments also give us opportunity to link and build power with others, who may or may not be or call themselves anarchists but who share the anarchic spirit for total freedom.

We think it is no accident that the height of the anarchist movement – to what ever degree we identify with that history – was precisely when it was an internationalist movement. Just as capitalism and state power are global – and generate global crisis – so too must the fight against it be.

Call for Anarchist Solidarity

We are calling for immediate acts of solidarity with rebels in Sudan (and against the Sudanese & Saudi state) – whether that’s banner drops, graffiti and wheat-pasting, informational tabling, rowdy marches & demos, fundraisers to help Sudanese doctors get medical supplies, or other creative acts of intervention that make sense in your context.

While this call is for immediate reaction we should be taking time to look at our local terrain to find private or state run entities with economic ties to the Sudanese or Saudi state and act against them to move our solidarity from what is most likely symbolic actions to show the people of Sudan they are not alone to a combative solidarity that impedes the smooth functioning of the TMC, the states that support and supply it, and the logistical flows of the supplies used to repress the uprising.

Solidarity is never a one off action, but a constant process of building relationships with other anarchists and movements for liberation, of examining, acting, and learning to build a materially effective practice of attack. International solidarity is key because Capital, it’s defenders, and it’s reaction fights globally and so should we.

Against Authoritarianism Anywhere

For Total Freedom Everywhere

Additional Resources on the Uprising

A Siege, Then a Storm: How Sudan’s Sit-In Was Cleared

Revolutionaries Call for Total Civil Disobedience After Massacre by Military in Sudan

Sudan Sit-In: How Protesters Picked a Spot and Made It Theirs

Algeria, Sudan, and the Arab Spring

On Shared Struggles: From Sudan to the Gilets Jaunes to #MeToo