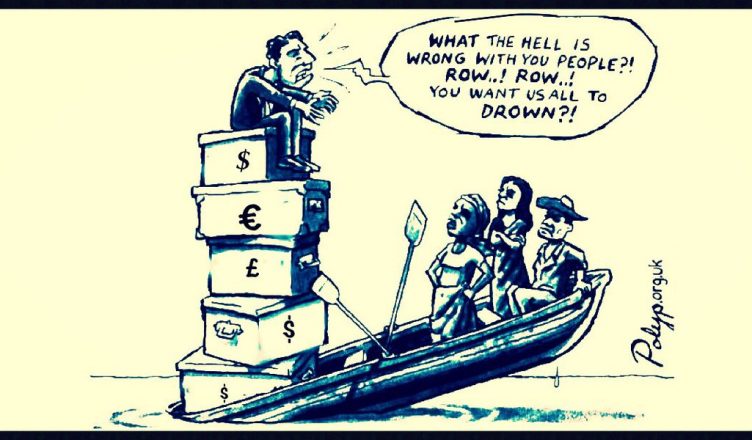

It

is a common tactic of states and capital to invoke the “national interest” and

“we’re all in it together” as a means of diverting attention from the class

war. Such cries were heard often during and after the 2008 financial crisis,

when states and capital protected themselves by turning the screws on workers.

However, the current situation with COVID-19 has certainly outdone the 2008

financial crisis in the pleas for national unity. Indeed there has probably not

been an occasion since the 2nd World War where the national interest has been

so successfully employed (at least in “the West”).

In the UK all parties and governments are largely in consensus, happy to echo this

call for unity, any division between Tory and Labour, liberal and conservative,

“leaver” and “remainer”, Westminster and Holyrood has been temporarily put

aside by the political classes. Journalists and politicians alike, backed

up by their tame experts and pet scientists, are happy to raise the myth

of WWII – a wartime footing for the NHS, the fight of our lives, etc – to make

the argument for unity. Of course the real divisions of society – between

labour on the one hand and capital and State on the other – are as present as

ever. The effects of this crisis will be felt disproportionally by the poorest

– both in the UK and worldwide.

The political consensus is rooted in the unanimity that there can be no more

damage to the economy, an argument reflecting the interdependence of the State

and capital. Contrary to claims of some social democrats, neo-liberalism has

not been a case of capital doing away with the State but rather the State and

capital becoming increasing integrated, capital requiring the State to

facilitate its exploitation of workers. The current crisis provides an

excellent example of this interdependence, with the State stepping in to ensure

the economy (i.e. the economic exploitation of workers) continues to function

in some manner.

To this end we have seen a series of increasingly interventionist budgets by

the UK government to deal not only with the COVID-19 situation but also the

demands of workers. As a result there have been some real, if limited,

concessions to labour – the covering of 80% of the salary of those workers on a

payroll will be welcome relief to some, however, it does nothing for those in

precarious employment and many of the lowest paid. And while the demands from

some for a “basic income” may have some advantages, particularly at the current

time, it would still be part of a series of measures designed to save

capitalism not to bury it.

However, despite their intentions, capital and the State may have a harder time

than they think in putting the genie back into the bottle. Even before, the

additional measures were taken because the COVID-19 crisis workers had forced

the 1st budget of this government to the “left” of any since at least

2008. While the conflict between liberalism, already weakened before the

pandemic, and (national) populism is currently taking a backseat, it seems

likely it will be renewed sooner rather than later. It is not hard to see that

the current crisis will feed into the increasingly anti-immigration political

climate. Neither liberalism nor national populism offer anything to labour

directly but the competition between the two may open opportunities to advance

the power of workers. In addition, to supporting worker self-organisation at

this moment it is vital that we also look forward to how we can keep and extend

any gains we make. To that end the nonsense of national unity, not “being

political” and workers and bosses being on the same side needs to be

opposed whenever possible.

Class War Not On Pause