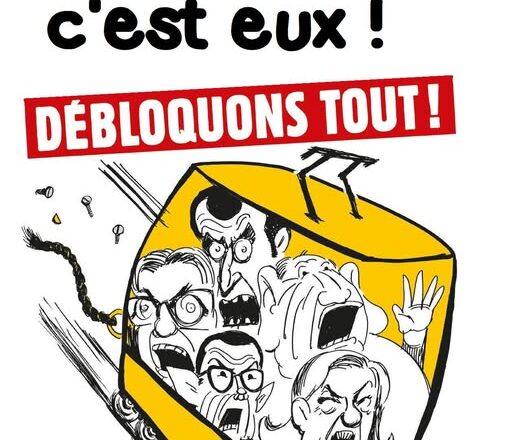

The Bloquons Tout (Block Everything) movement emerged as a viral phenomenon on the Internet and on various social networks in mid-2025. It was a result of the austerity measures announced by then Prime Minister François Bayrou. These included the abolition of two national holidays, a pensions freeze, and massive cuts to healthcare. The slogan “Boycott, disobedience and solidarity” (Boycott, désobéissance et solidarité) was advanced by about a dozen people on social media. They called for a total shutdown of France on September 10th, and people were encouraged to not go to work on that day, avoid road use, not shop at the big chains, keep their children at home, and occupy symbolic locations. It was a movement like the previous Gilets Jaunes (Yellow Vests) but far more openly radical, and involving a younger generation.

The government responded by saying this was a tiny minority movement, not able to deliver on its promises to mobilise. As the traction developed for this movement, the interior minister Bruno Retailleau was forced to make the usual old tired announcement on September 9th that it was a movement led by left groups, intent on violent action.

If September 10th wasn’t a complete success, failing to achieve its aim of paralysing France, it still mobilised hundreds of thousands of protestors. It indicated widespread social anger, and the willingness of young people to take part. This was despite severe police repression on the day, with 80,000 police and gendarmes mobilised nationally. The State forces used mass arrests (540 in total), rubber bullets, gas, drone surveillance, and the deployment of many armoured vehicles.

Despite this, hundreds of blockades took place. Whilst often quickly broken up, they turned into wildcat demonstrations and spread to other areas. By busting up the blockades, the police inadvertently strengthened picket lines. At Nantes, 150 protestors reinforced the picket line at Valo’Loire incinerator, and at the Amazon site at Bretigny sur Loire, where a strike was taking place, there was a similar reinforcement. It was the same at Airbus in Toulouse, at the Feyzin refinery near Lyon, at Le Havre, at the Montpellier railway picket, the Eugène Delacroix high school in Drancy, and at the Tenon hospital in Paris, which was joined by students from the Voltaire high school. At the Gare du Nord in Paris, despite a huge police presence, rail workers, workers from different sectors, and young people took part in a mass general assembly.

It wasn’t just the big cities where actions took place. Many small towns saw leafletting, blockades around roundabouts, commercial areas, or expressways. The government was forced to admit that 175,000 had taken part in the mobilisations, although this is a much smaller figure than counted by various organisations, with the CGT union reckoning on 250,000 participants.

In addition , several general assemblies took place at various high schools and universities, and this was before the start of the academic year. 500 students at Rennes, 250 at Paul Valéry, 300 at Jussieu, 200 at Paris-Cité, all in Paris, and 250 at Mirail in Toulouse. 150 high schools were blockaded. However, only 5% of teachers came out on strike.

Several tens of thousands marched in Marseille and 50,000 in Toulouse, including 5,000 in the youth procession, more than 10,000 in Lyon and Bordeaux, 10,000 in Rennes, 6,000 in Chambéry, 4,000 in Amiens and 2,000 in Aix-en-Provence. In Paris, there was no single demonstration, with thousands massing at Place de la République (several thousand), Place du Châtelet ( 10,000) and Place des Fêtes (more than 10,000). “The best part was there, in what remains one of the very last authentically working-class neighbourhoods in Paris. More than 10,000 people. Festive and lively music. The speeches were lost in the hubbub of a very young, diverse and joyful crowd, undoubtedly more politicised.” (report from a group of the Federation Anarchiste).

However, in some places there were much smaller mobilisations, as at Boulogne sur Mer where only 150 turned out.

In addition to blockades of educational establishments and at roundabouts, there were road disruptions with several ‘drive slow’ operations on motorways, as at Rennes, Nantes, on the A10 highway near Poitiers South, on the A9 at Aix-en-Provence, on the Toulouse beltway, on the A1 near Lille. In addition, peasants from the Confédération Paysanne agricultural union took part in blockades with their tractors in blockades, including the A20 highway, Chambéry, Bourges, and Albi. However, another agricultural union, the FNSEA, failed to take part in the mobilisation, offering the excuse that that grape harvests were still underway, herds were on their summer pastures, maize and beet crops were being gathered, and cereal sowing had begun. Instead, it said it was mobilising for a day of action on September 25th. The CGT union leadership failed to mobilise its members for the day, repeating its behaviour in May 1968. In some places, veterans of the Gilets Jaunes movement appeared, as at Abbeville where one interviewee said that he was taking out his yellow vest again because “nothing had changed”.

It remains to be seen whether the tempo of the mobilisations will continue and intensify. In some ways the actions were a dress rehearsal for September 18th, when the main unions are calling for mass strikes.

What is encouraging about the movement of Bloquons Tout are the large numbers of young people involved, and its decentralised nature, enabling it to mobilise in small towns and villages.